“Cue The Music” is a three part series examining the options available to amateur and semi-pro audio/visual producers who wish to incorporate music in their productions. Part one examines the process of clearing copyrighted music. Part two offers 5 alternatives to using copyrighted music. Part three examines the process of using royalty free music.

1. Introduction

There’s a whole wealth of music out there that could really enhance your audio/visual projects and impress your customers. But there’s a problem. Literally everything you hear on TV, radio, cinema and in bars and nightclubs is protected by copyright. And you will face a wall of expensive bureaucracy trying to gain permission to use it for your own ends.

But if you really, really think it’s the only option you have, this article aims to give you some insight into the process of using copyrighted music on a low budget project.

2. Let’s Suppose

Let’s suppose you get a job to produce a DVD about the fashion industry. Some of the footage features a catwalk show filmed at the Fashion Institute.

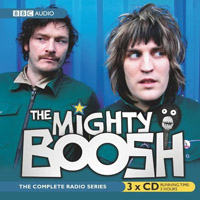

On the night, the PA system is pumping out Dr. Dre’s ‘Still D.R.E.’ at full volume. That’s fine. It adds a real hard edged atmosphere and sounds great as the models strut down the catwalk.

But here’s the thing. The venue will be covered by an annual blanket performance license that allows them to play copyrighted music whenever they like. Unfortunately, your DVD copies won’t be covered by the same license. If you leave the soundtrack as it is you will be breaking the law. Even for a small run, you need express permission to use a published works, even if it’s in the background. And let’s be clear. Gaining clearance to use copyrighted music on a low budget short run DVD project is quite an undertaking. Infact, that’s something of an understatement. Running into a minefield blindfolded would perhaps be a more accurate description! There are so many pitfalls and grey areas that it’s difficult to see why anyone would wish to even attempt such a thing in the first place.

Some people don’t get permission, of course. They just go ahead and use it anyway without asking. Chances are no one will see or hear their work, so they figure ‘why not?’. Well, that’s fine if you’re foolhardy enough to risk a massive fine or in extreme cases imprisonment. But if you’re serious about making a long and fruitful career out of audio/visual production you will need to address these issues head on.

So what I hope to do in this article is at least remove the blindfold, giving you a fighting chance in that minefield. Or perhaps even offer some of the options that are available that you may or may not have considered as alternatives.

3. The Grim Truth

Let’s start with the facts. The copyright on all published works is shared between a number of different institutions and individuals. Each of these parties will wish to be informed of your intensions before they decide whether to grant permission to use their copyrighted material.

You may think that obtaining permission will be the end of it. Not really. Each of these individual parties will want to be paid large sums for allowing you to use their copyrighted material for your own ends. And this is where the fun starts. You could find a very substantial amount of your narrow profit margin being siphoned off by unbelievably disproportionate advances and subsequent royalty payments to publishers and record companies attempting to claw back the large amounts of unrecuperated production costs.

Remember, their business is all based on economics. They will be completely oblivious to any point of view based simply on artistic or intellectual grounds. In other words, it doesn’t matter if the music looks and sounds great on your project. You won’t be able to use it legally unless they say “yes”. They own the copyright and that’s that.

4. A Glimmer Of Hope

I don’t wish to make it sound all doom and gloom.

What with the enormous amount of turbulence in the music market lately, institutions have had to wake up to the fact that they may have to act quickly to make some radical changes to encourage more income from a variety of sources in matters related to the usage and distribution of published works. In other words, they are trying to make it easier to gain access to their vast back catalogues for sync usage on various projects from major films to short run audio/visual projects like the one we have in mind here.

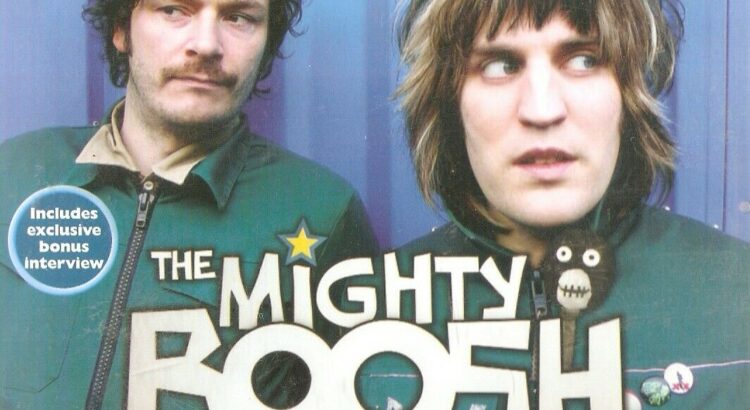

|

| The Mighty Boosh audiobook. Published music was replaced in post production |

Take into account the new range of ‘blanket licenses’ issued by the UK’s royalty collection agency, MCPS. (more on that later). But it’s tiny steps not giant leaps. There is still lots and lots of bureaucracy involved, especially on behalf of the record labels.

Having said that, if you’re still determined to use copyrighted material by artists like Dr. Dre on your DVD project, let’s take a look at how you go about it.

5. First Contact

First you’ll need a copy of the track, so dig out your copy of Dr. Dre’s ‘2001’ album. Look at the printed information on the recording. Somewhere in very, very small type there will be the name of the publisher attached to the familiar ‘c in a circle’. This is who you need to contact to get permission to use the composition itself (the synchronization rights). The lyrics, the instrumentation, the musical score. Sure, the songwriter(s) owns the rights to the song, but generally they grant those rights to a “music publisher” to administer them, and that’s who you need to contact.

OK, so we have found the name of the publisher. Right next to that there will be a letter ‘p’ in a circle followed another company name. This refers to the physical sound recording of the composition. That copyright (the master rights) is owned by the record label. In this case Interscope. If you want to use a specific recording of a specific song, you will need permission from the publisher of the song ‘Still D.R.E.’ and the owner of the physical recording of that song, the record company, Interscope.

You will also need the title of the song (Still D.R.E.) and the name of the composer. In this case Andre Young (Dr. Dre’s somewhat less imposing birth name).

Armed with this information you will first need to find contact details for the publisher. The easiest way to track down music publishers is through the performing rights society. All songwriters and publishers need to be a member of that society in order to collect royalties. Unfortunately, the performing rights societies will only give out the publisher information for the writers they represent. Therefore, if you want to use a song written by writers from different societies, you will need to go to each society’s website to find all of the publisher information.

|

| Dr. Dre’s ‘Still D.R.E.’. A hard act to follow? |

However, once you have tracked down the publishers contact details you will need to approach them directly to ask for permission. For this you will need to send a letter or email. Use the term ‘Independent Film Request’ or ‘Low Budget Project’, something that immediately outlines your situation and intentions. Reference the title of the song and songwriters, then the name of your production. Tell them briefly about the production how the song fits in, as well as the duration of the music and a description of the accompanying visuals. They will also need to know the territories in which your product will be available and the amount of copies earmarked for the initial run.

As for approaching the record companies, The bigger ones use central offices that deal with these kind of queries. But the smaller record companies are much easier to find. Generally their websites have all the contact details you will need. Once you get these details, approach them in a similar way to the publishers.

6. Licensed To Ill

With that thought in mind, Royalty collection companies such as ASCAP (USA) have recently introduced ‘blanket’ licensing schemes that allow copyrighted music to be transmitted unconditionally in certain circumstances. Although these kind of high end licence deals are way beyond the likes of you and me, a similar approach is beginning to immerge to help smaller businesses, too.

Take for instance the AVP (Audio Visual Product) license offered by MCPS in the UK. This is targeted at small budget short run video/DVD productions where music is used, but is not the primary theme of the product. A class that they term ‘non-music’. (A fitness video, a sports event or a drama is OK. A concert or music chart show is not OK.). Our ‘fashion show’ project should fall into the category ‘non-music’, because music is not the primary theme of the presentation. It’s a fashion show using music as enhancement and not as the main theme. So in this case, an AVP license may be suitable.

The license removes the need for separate sync payments on each individual piece of music, favouring a ‘blanket’ license covering the whole project. But take into account that this license refers to the copyright of the composition and NOT to the sound recording itself. (As we’ve already determined, the physical copyright is owned by the record label). Take into account also that under the terms of the license agreement and for granting usage of their part of the copyright, MCPS will still want to skim off a whopping 8.5% of the highest published dealer price. So you kind of inherit a cash-hungry business partner as well as a license and that’s gonna eat into your profits in a big way. As a footnote, other royalty collection companies may have their own similar blanket license agreements. The AVP license is merely an example.

7. The Waiting Game

So you’ve sent out your letter or email to the publishers and the record company requesting permission to use their copyrighted material in your project. Getting a response to your initial query is going to take time. Especially in the case of the record company. Permission for small time usage is pretty low on their list of priorities and this is often reflected in their response. It may take ages and ages for them to say “no”. Or simply come up with some ludicrous figure of tens of thousands of bucks that you couldn’t possibly even consider.

On the upside, the chances of the publishers granting permission is marginally higher. This is after all their reason for existing. To license and promote the work of the artists that they represent. And in the case of the AVP license mentioned above, you are able to apply for permission relatively painlessly using an online application form.

8. What Happens next?

You will certainly need to follow up your query. But leave it for at least 14 days before you do. Beyond this point I’m afraid it’s in the lap of the Gods. You have followed the procedure that begins the process of clearing rights to use copyrighted music on a small-run DVD project. The outcome is entirely dependent on all parties agreeing to grant permission. You’ve got a reasonable chance of gaining rights from a publisher to use a composition. But precious little chance of being granted rights from the record company to use that specific recording. And no chance at all of being able to carry out all this administration before your deadline. If I were you I’d be investigating some alternatives. And that’s just what we’ll be doing next. Looking at all the options available to you when substituting copyrighted music with licensed music on a low budget short-run audio/visual project. All coming up in the next part of Cue The Music.

9. To summarize

To use copyrighted music on a low budget short-run DVD project you will need to apply for permission from two sources. The music’s publisher and the copyright owner of the physical recording of the composition (normally the record company).

Many royalty collection agencies now offer blanket licenses that provide easier access to synchronization rights. The license cost may be negligable, but the royalty demands will narrow your profit margin. Rights to use the physical recording will be the hardest to obtain and may be accompanied by a request for a large advance plus subsequent royalties.

Resources:

ASCAP: The American Society Of Composers, Authors and Publishers

MCPS: The UK’s mechanical Rights society

Comprehensive international list of royalty collection agencies

More in this series:

Cue the Music, Part 2: Top 5 Music Resources On A Budget

Cue the Music, Part 3: Royalty Free Music Under the Microscope