Let’s go to eleven

Let’s go to eleven

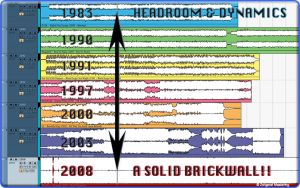

It is common professional practice for a mixing and mastering engineer to normalize tracks and apply the proper compression to maximize the punch of sound: it’s called loudness, or the loudness wars. This is the skills and tactics of skilled sound engineers and the reason why musicians like myself hire experts who spend their lives studying the art of music mixing and create gorgeous sounding tracks that have “radio quality” and tracks that can be played – and will sound good – on any system, from iPhone speakers to arena speakers. After sound engineers work their magic, a track can be played on any system and the result is the same: basically, it sounds really good with impact and depth. When “mastering” a track, engineers apply compression and limiters and equalizers and the master track becomes perceptually louder. The proof is in the perception, one can hear the solid power of the finished work. As this image shows, the size of the .wav file, amped through science and expertise, results in more breadth given to the visual image of the file itself:

Let’s give the .wav file a haircut

After twenty years of staring at my Logic Pro project files and zooming in on .wav forms, I am very familiar with the above image. As a novice mixer years ago, I was under the similar naive impression as some A&R reps are: the bigger the .wav form, the better the sound. This is simply not true. Like the image below, slamming compression onto recorded sound is akin to a bad haircut as much of the nuance and art is gone. Like a “bowl cut” that parents used to give their kids (put a bowl around the head and cut around it), over-compression increases the auditory flatness of a track. Hilariously, to me, I still remember my early days in digital mixing when my friend and I used to scream “haircut” in delight when compressing a track and watching the .wav form change. To our horror, after a few days of recording and attempting to mix, the tracks sounded terrible and it took me a few (many) years to understand why. This image explains it all:

This same knowledge that these professionals use when mastering music, sound effects and sound for film has also become an arena of competition known as the “Loudness Wars” – which is essentially a decades old rivalry between sound engineers throughout the world seeking to give their work a sonic advantage. If your track sounds louder than the rest, is bigger than the rest, then it stands out, which could give an economic advantage. Related, have you ever watched television and noticed that the commercials are suddenly much louder than the show itself? I have, and it is jarring. Clearly, the advertisers want to BE HEARD!

It all started back in the day

The sound wars can be traced back to the 1940s when jukeboxes that played 7-inch records were popular. Owners of the jukeboxes could set a standard volume for the machine, and therefore any tracks that had been mastered with skill would be “louder” would prominent over the others. Naturally, studios and record companies requested and demanded mastered singles that were louder than their competition. A competitive spirit also emerged between artists in the 20th century as compilation CDs and radio play demonstrated which tracks were “hot” and which were weak. The increase in volume is demonstrated by this image of the wave file for Michael Jackson’s “Black or White,” which was remastered over the years. One can visually see how the size of the wave file of Jackson’s master track increased over the years from 1983 to 2008.

To make it loud just kill the dynamics

Austin Statesman quotes a letter written by Angelo Montrone, a vice president for A&R for One Haven Music, a Sony Music company: “There’s something . . . sinister in audio that is causing our listeners fatigue and even pain while trying to enjoy their favorite music. It has been propagated by A&R departments for the last eight years: The complete abuse of compression in mastering (forced on the mastering engineers against their will and better judgment).” Statesman goes on to state that major record labels have a mistaken belief that any record that is extremely loud will automatically turn the song into a major hit and bring in nice profits. Montrone calls this an “aural assault” on the listener because all the dynamics have been eliminated. Statesman goes on to make the point that the over-compression of current music wears out the listener. While the audience might like the music, they experience sonic fatigue and stop listening because the loudness is inexplicably offensive to their ears and minds.

Metallica’s unfortunate mixing “whoops”

As explained in “The Loudness Wars: Why Music Sounds Worse” by NPR on their program “All Things Considered,” a perfect example of the dangers of creating painful music through over-compression involves one of my favorite bands of all-time, Metallica. Their “Death Magnetic” album of 2008. The record was released at the same time the music was available on “Guitar Hero” and fans were able to compare the compressed music on the album to the tracks available on the game, which were not compressed. There was an outpouring of fan feedback, including an online petition signed by over 10,000 plus fans suggesting that the band remix the album. The music on “Guitar Hero” was significantly more palatable than the record itself. This is not the band’s fault, rather, the record label clearly suggested that final mastering sound engineers apply maximum compression which resulted in an inferior product. The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in Europe is an agency that has standard measures for loudness and claims Metallica’s album is one of the loudest ever created. Master sound engineer Bob Ludwig, interviewed in NPR’s piece, states that in addition to pirating downloads, the sound war is one of the greatest contributions to declining record sales.

As explained in “The Loudness Wars: Why Music Sounds Worse” by NPR on their program “All Things Considered,” a perfect example of the dangers of creating painful music through over-compression involves one of my favorite bands of all-time, Metallica. Their “Death Magnetic” album of 2008. The record was released at the same time the music was available on “Guitar Hero” and fans were able to compare the compressed music on the album to the tracks available on the game, which were not compressed. There was an outpouring of fan feedback, including an online petition signed by over 10,000 plus fans suggesting that the band remix the album. The music on “Guitar Hero” was significantly more palatable than the record itself. This is not the band’s fault, rather, the record label clearly suggested that final mastering sound engineers apply maximum compression which resulted in an inferior product. The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in Europe is an agency that has standard measures for loudness and claims Metallica’s album is one of the loudest ever created. Master sound engineer Bob Ludwig, interviewed in NPR’s piece, states that in addition to pirating downloads, the sound war is one of the greatest contributions to declining record sales.

Can we return to the golden age of sound?

In recent years, some claim that the loudness war may soon be over. Roy Dykes in “Making it Louder: Are the loudness wars almost over?” at least hopes so. He claims that according to mixer Bob Katz, some labels have begun to make different masters for CDs (which are nearly a thing of the past) and online outlets. Frankly, it would take a consensus among all parties involved to solve the over loudness problem. Dykes advocates that going back to less compression in order to enhance music dynamics is a conscious choice that musicians, mixers, and labels will make in the future. I certainly hope so. Though it will be a challenge.

As a musician myself, it certainly would be difficult to request that a mastering studio make my tracks softer to preserve dynamics when I know that they will pale in impact in comparison to the work of other artists. Just maybe, like the free markets in any industry, customers will en masse and unconsciously decide which level of “loudness” and compression is on point. Through the power of purchasing, hopefully, consumers will be able to dictate the direction of the mixing industry. Personally, I know that when I rarely put on vinyl through my old DJ turntables, I am blown away by the quality of the sound, the vibrancy of the bass and the crystal treble. To put it simply, vinyl just sounds so good – especially after years now of listening to CD’s and downloadable audio.

In the end though, its the song and music that counts: the melody, the lyrics, the instrumentation and the human voice. A piece of music of genius proportions will move the listener when played through nearly any medium. Compression and the negative aspects of the loudness war certainly matter, but fortunately, in the end, it is the music that counts.

You can find high quality music recordings in the Shockwave-Sound stock music library. Any track purchased and downloaded from Shockwave-Sound comes with a license to legally use the music in media, film, games, apps, and more.

Let’s go to eleven

Let’s go to eleven